Public privacy: Lin jingjing's works

Gu Zhen Qing

Public privacy usually refers to individual privacy and privacy rights in public settings. Privacy refers to concealed, non-public affairs. Individual privacy touches on individual rights and an individual’s secrets, things that have nothing to do with other people. Individual information, private affairs and the individual realm are things that the individual is unwilling to reveal to others, or to have others intervene in; these are privacy rights. In today’s globalized, networked world, individual privacy and privacy rights are in danger. A side effect of technological progress has been that the public sphere is no longer limited to physical public spaces. Public information platforms, urban surveillance systems, internet monitoring, candid street photography, human flesh search engines and hacker attacks have all become methods, both positive and negative, for breaking down the boundaries of privacy. This has made individual privacy increasingly transparent, something that the public can give or take away, something that can be revealed at any time.

With her feminine sensitivity, Lin Jingjing has found within her own childhood an anxiety derived from individual memories and privacy. She has become aware of individual privacy’s inability to resist the public world. When individual privacy encounters the public setting, it faces the danger of being invaded or swallowed up at any moment. As an artist Lin Jingjing’s societal role is to create artworks, present them and reveal their secret import. The artistic exhibition space is a fully exposed stage, a completely public setting that every artist must face. For this reason, the weakness or danger of individual privacy alluded to by the concept of public privacy has become the focus of Lin’s insight into the relationship between the individual and society.

In November 2009, the Song Zhuang Art Museum exhibited Lin’s 2007-2009 installation series I want to be with You Forever and Never Apart. These works used hundreds of wedding photographs taken from wedding photography studios and the artist’s friends as social survey visual research material. Lin’s photographic alteration techniques were low-tech, manual, even crudely interventionist. In each photograph, she forcefully removed one of the people from each of these intimate spaces and placed them into different spaces. In I want to be with You Forever, Lin used miniature toy wedding beds. These identical European-style white wire-mesh wedding beds bore obvious traits of the consumerist culture inherent to China’s social transformation. She took the five inch wedding photos, with one person removed, and sewed them into the fine wire mesh of the toy bed, while the other person from the photo was sewn alone onto the canopy of the bed, directly above its cutout silhouette. Since the two images were aligned, when the viewer looked down from above, the two subjects of the wedding photograph were still together, albeit separated by a fine wire mesh. In Never Apart, Lin used cheap compact mirrors. The external casing of the compact mirror is a joyful image of a peony flower over a red background, and the edges are lined with gold geometric markings. The brides and grooms of the wedding photos have been placed on opposing sides of the mirrors in their original positions. With the mirrors open to 90 or 100 degree angles, it appears as if the brides and grooms have been reunited in their reflections. Lin uses the dismantlement of these wedding photos to express her skeptical attitude on the union and disunion of male and female relationships in the contemporary marriage. The use of hundreds of tiny wedding photographs of unknown couples represents a grand narrative of size and scale. Another trait of public privacy emerges through the constant probing of Lin Jingjing’s artistic imagery. These countless private photographs of men and women, owing to their repetitive poses, stiff postures and identical expressions, have been wiped of individuality, and for this reason it does not amount to the exposure or revelation of any particular individual identities. Public privacy is also a process of the formatting of privacy. If the private subjective is not brazen, and the public does not track down individual cases, then the monotone individual privacy is submerged within the planned and designed social realm. Though this individual privacy repeatedly emerges in the public setting, it blurs the public gaze to the point where it is no longer seen.

In her early years, Lin Jinjing concentrated her efforts on painting, creating oil paintings of skirts and signs with a freehand technique. As she honed her artistic practices, Lin,as a woman artist, she often experimented with inserting once tightly held private details of life into her works, presenting them to public society through metaphor and symbolism. In fact, within the artist’s experiences, not only the body’s characteristics, private life and private habits but even private diary entries, photo albums and communications, all of these things that belong to the realm of privacy rights, become a series of convenient and rich resources that the contemporary artistic spirit cannot ignore. If self-concealment is the right of the individual, then self-exposure and self-expression are also individual rights. For this reason, Lin has been trying to break the taboos of privacy to look upon the self and the world truthfully and objectively. She is bent on forcing certain individual privacies to encounter the public sphere and become public privacies.

From 2001-2002, Lin engaged in a year-long photographic diary series entitled My 365 Days. She placed the hairs that fell out of her head each day into a bowl and took a photograph as documentation. What appeared to be a random stream of photographs was actually marked by temporal qualities, laying bare a woman artist’s sense of helplessness and emotion in the face of her passing youth. The lack of emotion found in the simplicity and unity of the image style evokes traditional aesthetic imagery of the unforgiving march of time. This exposure of privacy and her cool attitude towards the brutal reality of one’s fading youth are things that come from Lin’s heart. This led her to a deeper understanding of more contemporary art concepts and opened up new means of expression.

Afterwards, Lin Jingjing’s painting language grew more open. Her Diptych series of 2005-2007 recreated public images that were popular during the Cultural Revolution, and brought them into the imagescape of everyday life as flourishing touches in the foregrounds or backgrounds of figure paintings. This individualized reproduction or transplantation of public images from history is perhaps linked the artist’s personal memories. With their lack of defining traits and their Cultural Revolution-era clothing, the figures become striking collective memories. It was precisely this call to remembrance and cultural introspection that brought Lin’s diptychs beyond expressive forms and towards the conceptual.

The 2007-2008 photographic series I Want to Fly was an effort to bring her individual creations on the track to systemization. It was as if she directed, shot and produced a group performance art piece. She repeatedly set up a camera and asked the young people around her to jump in place in front of buildings marked for demolition or construction sites. Each photograph presented one person. The low camera angle placed the people in the sky. She then cut out each person from the resulting black and white photograph and attached them and the separate backgrounds onto opposing book pages made of cotton. The soft cotton sticks out from the edges of the cutout pictures, creating a sense of floating people within the empty silhouettes. Among the different poses, some of the people appeared to be flapping their arms like birds. Lin placed the hollowed-out photographs on the right side of the cotton page, with the figures on the left side. On the left, the leaping figures removed from their surroundings floated in solitude above the cotton background, like symbols removed from reality, metaphysically floating, carrying Lin’s cultural idealist yearning to escape the fetters of the world and fly off into the distance. Flight is the realm that Lin Jinjing has always sought in life. In having normal people open their arms and jump in place, she is actually trying to let them escape their increasingly mechanized jobs and trivial everyday lives to experience a moment of transcendence. Those flying white silhouettes are suggestive blank spaces which the viewer can interpret as multitudinous avatars of the artist or can project themselves into, to imagine a moment of flight. On the surface, Lin’s projective empathetic method appears to be an expression of the generosity that is unique to female Chinese intellectuals, but in fact, it is the artist’s systematic attempt to create individual style and imagery in the language of photographic installation.

Lin Jingjing’s empathetic method is even applied to inanimate objects. In the Rose, Rose photographic series, she uses red string to stitch the rose petals together on the bud, and presents the intricate stitches and wounds on the flower petals through massive, high-resolution subjective pictures. The pain alluded to in these vivid details is frightening. The artist uses a subtle, intentional harming of beautiful objects to allude to mankind’s violent destruction and exploitation of nature. Her Dress - Rose series forces roses into women’s clothing, further anthropomorphizing roses. Her 2006-2011 Dress series is an effort to use beautifully exquisite wedding dresses and silk gowns as visual mixed media materials. The minutest details of those beautifully laced garments are laid out to create desolate imagery, like a series of bodies emptied of all spirit. The coldly beautiful images are alluring, yet viewers dare not look too closely.

Privacy rights are a product of modernity. They have been broadly affirmed by civil society as god given human rights. It was because of this that they were enshrined in legal shields and moral screens. But the Talmud said long ago that there are three things man can never keep private: a cough, poverty and love. Under globalization, privacy is finding it increasingly difficult to hide from the increasing pervasiveness of mass culture and the eyeball economy. The screen of privacy is often warped and twisted, worn thin and brittle. For Lin Jingjing, once privacy can no longer conceal that which the artist most wishes to conceal, then revealing private memories, private emotions and independent awareness to the public become her best methods of protection. For this reason, public privacy is no longer a passive concealment but an active revelation and sharing. Public privacy is a way of replacing private privacy, and solution to media’s penetration of the deepest levels of privacy. When some people’s secrets can be shared and turned into public information, public affairs and the public domain, then the private privacy becomes an unspoken open secret. When many people see the telling of individual secrets as a means of relieving stress, then below this surface of sharism, each person will find better concealment for a deeper level of privacy.

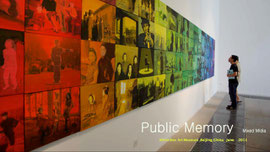

In 2008-2009, Lin Jingjing further probed the collective and private memories in her individual experience, creating the two photographic installation series Private Memories and News Memories under the theme Nobody Knows I was There, Nobody Knows I was Not There. Ambiguous and equivocal definitions of public privacy are controversial, but Lin finds clear, dualist values judgments to be useless, and feels that more ambiguous approaches can reach closer to the truth of public privacy. Her passion for paradoxes grows ever stronger. She has incorporated highly perceptive paradoxical thinking into her methodology, infusing her artworks with a personalized sense of form. In 2010-2011, she pushed this paradoxical theme a step further with her Public Memories series of oil paintings.

Private Memories is actually a single photographic installation, a collage of photographs collected from her relatives that span the breadth of the 20th century. Lin Jingjing used an old-style Chinese medicine chest with 90 drawers to present these private photographs of various sizes, lining each drawer cavity with cotton and placing only one photograph in each. Some of these dusty, yellowing photographs are studio family portraits, some are individual portraits, some are passport photos and others are commemorative group portraits. They come in many forms, but all of the people in them are related to Lin Jingjing in some way. Lin views these photos as both a visual family tree and as a precious collection of materials regarding her own life. Drawing from her thinking on public privacy, she has gouged out the faces of all the people in the photographs. As a result, each of the figures in these pictures has a gaping hole in a key place. With the faces removed, the uniquely private properties of these images have disappeared. What remains is lifeless clothing, furniture, buildings and scenes. The figures may be empty shells, but viewers fill them in with the artist’s own portrait. After all, they are all Lin’s relatives, so they must look like her. Genetic references turn all of these photographs into Lin’s avatars. It is as if Lin has used the cycle of life to lead the viewers into experiencing the trying times and glorious moments of the last century. Her arbitrary method of concealing her family’s privacy led to a unique image expression form, turning the artist into a chameleon who can pass through history and life with the utmost of ease. Perhaps it is this dreamlike, indefinite quality of her imagery that leads her to exclaim “nobody knows I was there, nobody knows I was not there.”

Lin Jingjing’s News Memories series uses images derived from CCTV news reports. Her selection criterion was that the image must contain a central figure as well as a crowd. As a result, most of the images are related to Chines official political gatherings and coverage of political life. One after another ritualized collective event is brimming with ideological atmosphere. Lin has removed the face of the core figure in each image, and then stitched each image – minus the face – onto a porous metal box, which is then covered with a lid marked with the Coca-Cola logo, in an allusion to the conflict between the right-leaning consumer society in the background and the left-leaning ideological imagery at the center. In the faceless figure, there exists the logical paradox of simultaneous presence and absence. The true visage of that core figure is already absent, becoming a public privacy intentionally created by the artist. Though the specific individual has been concealed by the artist through subjective methods, as long as the profile is there, he is still the core of the image. When the different profiles are placed together, they take on shared properties, becoming what is apparently an omnipresent, headless big brother who appears in different public settings with different poses and bearings. Lin’s intention is to use this to examine the collective unconsciousness of the public memory. The result of omission is often public approval. It doesn’t matter who that core figure is. What matters is that there must be such a core figure in every crowd.

The 2010-2011 Color of Memory series is a work that Lin Jinjing derived directly from individual secrets. She devised three questions regarding pain to ask of friends around her willing to share their secrets: 1, what is your most painful memory; 2, what object is connected to that most painful memory; and 3, what color best describes that most painful memory? Lin then creates a painting according to those answers, giving each painting a certain color and certain object. The key element of this artwork is the process of transforming individual secrets into public privacy. By placing concrete, everyday objects together with abstract colors, the artist has turned private memories into metaphor-rich symbols. These visual symbols cast doubt on and ridicule the increasingly superficial symbolic cognitive mode that is created by public privacy. Individual secrets have nothing to do with public or group benefit, but when private secrets are turned into public privacy, they become inextricably linked to public benefit. Perhaps this is Lin Jingjing’s thinking regarding privacy.

公共隐私:林菁菁的影像记忆

顾振清

公共隐私一般指公共场合的个人隐私和个人隐私权。隐私就是隐蔽、不公开的私事。个人隐私涉及个人利益、个人生活的秘密,和别人无关。而个人信息、个人私事、 个人领域不愿也不便他人知道、干涉和入侵的权利,就是隐私权。这种个人隐私和隐私权在当下全球化、网络化的全媒体时代,已经变得岌岌可危。作为科技进步的另类结果,公共场合已经不限于公共场所、公共信息平台,全城摄像监控系统、网管、随手拍、人肉搜索和黑客入侵已经成为公众穿透、干涉个人隐私壁垒的正反两种手段,这一切让个人隐私日益透明化,成为一种公众可以予取予夺、实时披露的社会现实。

出于女性的敏感,林菁菁从自身成长中领略到一种来自个人记忆和隐私的焦虑。她意识到个人隐私在公共世界中不可对抗性。个人隐私一旦遭遇公共场合,随时就有被入侵、被蚕食的隐忧。而林菁菁的艺术家身份,又决定了她从事的创作作品、展示作品、披露作品隐秘内涵的社会行为。艺术展览空间又是艺术家不得不面对的一种全无遮蔽的环形剧场、一 种彻头彻尾的公共场合。于是,公共隐私所预示的个人隐私权的脆弱感和高风险,就成了林菁菁洞察的个人与社会关系的焦点。

林菁菁2009年11月宋庄美术馆个展中展出了2007-2009年系列装置《我要永远和你在一起》和《永不分离》,作品使用了艺术家从朋友处和婚纱影楼随机征集来的数百张婚纱照样片,作为一种社会调查式的影像素材。林菁菁的影像改造手段是低科技的、手工的、甚至是粗暴干 预式的。她只是用利器,把这些婚纱照上亲密无间的男女主角中的一个形象整个裁出、挖走,置于另一个空间。在《我要永远和你在一起》中,林菁菁借用了迷你型 的玩具婚床。这些统一欧陆风情制式的白色铁丝制婚床具有浓郁的中国转型期社会的消费文化特征。她把含有镂空形象的5吋婚纱照片缝合、固定在格栅密致的丝网式床 榻之上,主人公的缠绵对象是一个被挖空的剪影。而被挖出的另一主人公形象则缝合、固定在穹形床顶之上,形只影单。由于图像位置的对应关系,在观众俯视的角 度下,被强行分离的一对婚纱照主角形象又恰巧契合在一起,只是隔了一层密致的丝网格栅。在《永不分离》中,林菁菁则采用了一批廉价的便携式双面补妆镜盒。镜盒外壳为喜庆的大红底牡丹花图案,镜面框架则为艳俗的金边几何纹饰。被分置的婚纱照男女主角按原来的组合位置各据一个镜面。由于镜盒处于90度至100 度角打开状态,所以,面对观众,男女主角又在彼此映照的镜像中重逢、复合,虚拟出两个的近似破镜重圆的假象。林菁菁利用婚纱照影像的拆解,挑明了对当代婚 姻所牵连的种种分分合合的男女关系的一种质疑态度。由于她征用数以百计的未知男女微观化的婚纱照图像,构成装置作品集合化、规模化展示的宏大叙事。公共隐私的另一个特征就在林菁菁艺术语境的不断拷问中浮现出来。无数男女的隐私图像,由于姿态划一、动势僵硬、表情重复,反而屏蔽了个性,无法构成针对特定个人信息 的曝光和披露。公共隐私也是一种隐私格式化的过程。如果隐私主体个性不张扬,公众又不追究个案,千篇一律化的个人隐私也就会淹没在被设计、被规划的社会规 范之中。即便这类个人隐私在公众场合反复出现,也会让公众焦点模糊,熟视无睹。

林菁菁早年执着于绘画,以写意手法画了一些裙子和符号的油画。随着自身艺术实践的历练,作为一个女艺术家,她却常常尝试把以前不愿让他人知道的个人生活隐私纳入作品之中,以暗喻、象征的方式公开表达给公众社 会。其实,艺术家的个人经验之中,不但身体特征、私生活和私人习惯,而且个人日记、照相薄、通信等,所有这些原本属于自己隐私权的内容,却是建构当代艺术 精神不容回避的一座座最便捷、真切的资源富矿。既然自我遮蔽的隐私权是一种个人权利,那么,自我曝光、直白表达也是一种个人权利。于是,林菁菁尝试打破隐 私禁忌,真实客观地看待自身、看待世界。她执意要让某种个人隐私遭遇公共场合,成为公共隐私。

2001-2002年,林菁菁实施了一个为期一年的日记体摄影作品《我的365天》,她每天把掉落的头发放在一个空碗里,再拍一张照片作为记录。看似流水 帐的集合摄影却有时间记录的特性,完全清空一个女性艺术家对韶华易逝的无奈与感怀。简约、整一的图像风格传递出的零度情感,转述了一种落花有意、流水无情 的传统美学意境。这种晾晒隐私、坦然面对自己青春远去之严酷现实的气度,来自林菁菁心中的内驱力。这也促使她领略更多当代艺术理念,开拓更多表述方式。

后来,林菁菁的绘画语言也变得更为开放。她的2005-2007年的“双联画系列”再现了文革时期流行的一些公共图像,并把这些图像融入到日常生活的图景 之中,成为人物前景或背景中的一些点缀。历史上的公共图像的个性化再现与移植,也许跟艺术家的私人记忆有关。由于画中人物没有具体相貌,她们具有文革时期 衣着特征就构成一种鲜明的集体记忆。正是这种记忆的唤醒和文化的反省,使林菁菁的双联画越过表现主义样式,指向某种观念。

2007-2008年的摄影装置系列《我要去远飞》是林菁菁把个人创作纳入系统化轨道的一种努力。她几乎是导演了一批群众演员的行为表演,并进行现场拍 摄、后期制作。她不断设定相机机位,即随机邀请一些身边的年轻朋友在待拆迁建筑、地盘工地之前起跳。一张照片表现一个人。由于相机机位较低,跳跃的人被定 格在空中。林菁菁再把每张黑白照片上的人物形象按轮廓线抠挖下来,分别缝合在一本摊开的用棉花制作的白色书本之上。棉花质地柔软,于是就在照片被挖空的剪 影中膨胀鼓起,形成一个浮凸、飘忽而空洞的人形。由于人形姿态各异,有些人形居然构成了一种鸟儿飞翔的姿态。林菁菁把这种镂空图像置于棉花书本的右手页 面,而挖下来的人物则缝合于左手。左手边,那一个个失去了具体环境的跳跃人物孤悬在棉花纯白的背景之上,犹如一种脱离实际、形而上的飞翔符号,寄托了林菁 菁摆脱俗世羁绊、谋求远走高飞的文化理想主义追求。放飞自己一直是林菁菁孜孜以求的人生境界。她让普通人张开双臂、在现实生活中原地起跳,其实也是想让他 们脱离一下日益机械化的工作和一地鸡毛的日常生活,体验一刻超越现实的心境。那些飞翔的白色人形其实是一种填空暗示,观众可以将其理解为林菁菁的千百个化 身,也可以产生一种对号入座的心理投射,幻想一次自我的腾跃和飞翔。林菁菁推己及人的移情模式,表面上是中国知识女性一种泛爱主义的特有表现,实质上却是 艺术家在影像装置语言上营造个性风格、打造个人符号的一次系统尝试。

林菁菁的移情模式甚至还推己及物。在系列摄影《玫瑰•玫瑰》之中,她用红色丝线缝合玫瑰花朵,并以巨幅的、高清晰度的主观画面展示花瓣上精细的针脚和细微 的创伤。生动的细节所暗示的一丝疼痛感,让人心悸。艺术家利用对美好事物的极细微的人为伤害,暗喻了人类对自然环境的一贯暴力摧残和索取。她的《玫瑰物 语》系列则把一些女性衣物强加玫瑰花朵之上,让玫瑰的形象进一步拟人化。2006-2011年的《物语》系列,则是林菁菁把一件件精美婚纱、绸缎礼服当做 视觉元素和综合材料,直接制作平面装置作品的一种努力。那些精致的蕾丝花边的婚纱、礼服,以极为苍白的形象纤毫毕现地罗列在画面上,犹如一个个被抽空了精 神和灵魂的人物躯壳。略显凄美的图像却产生了一种令人唏嘘却又不忍细看的接受心理。

隐私权也是现代性的产物。它被作为天赋人权的一种权利而受到当代公民社会普遍肯定。由此,个人隐私才真正确立在法律的挡箭牌和道德的屏障之下。但是《犹太 法典》早就说过:人不能隐藏三种东西:咳嗽,贫穷,以及恋情。全球化条件下,私人隐私面对公众社会和眼球经济的无孔不入的挑战,越来越难以隐蔽。隐私权的 屏障时常被扭曲变形、变得薄如蝉翼。对林菁菁而言,一旦私人隐私不能屏蔽艺术家最想屏蔽的对象,那么,面对公众,公开私人记忆,披露私人情感,分享独立意 识,反倒成为她的一种自我保护的方式。因此,公共隐私不再是一种被动的隐藏,而是一种主动的打开、披露和分享。公共隐私成为私人隐私的一种替代方式,反而 变成全媒体时代各种深层隐私的解决方案。当一些个人隐私可以分享,成为公众共有的信息、事务和领域之时,这些私人隐私就成了公众心照不宣的公开化“隐 私”。 当许多人都把倾诉、公示部分个人隐私当作是自我减压的一种方式时候,其实在分享主义盛宴的表象之下,每个人另一些更深层次的隐私也就得以潜伏和隐蔽。

2008-2009年,林菁菁继续挖掘个人经验中的集体记忆和私人记忆,以“没有人知道我在那,没有人知道我不在那”为主题连续创作了《私人记忆》和《新闻记忆》两 个系列的影像装置作品。涉及公共隐私骑墙、模棱两可的定义,各种争论始终没有熄灭。但林菁菁偏偏觉得这种非此即彼、二元对立的价值判断不可取,而非此非 彼、否定之否定的思辩反倒接近公共隐私的真相。她越来越热衷于悖论,并把极具感性色彩的悖论思维贯注在方法论之中,从而赋予作品一种个人化的形式感。 2010-2011年,她又在这一悖论式的主题下推出一批《公共记忆》系列油画。

《私人记忆》其实是一个单一影像装置,它是艺术家回老家收集一批横跨1900年至2000年上一个世纪的自己血亲家族的老照片并置而成的作品。林菁菁用一 个拥有90个抽屉的老式中药柜来陈列这些大大小小私人照片,每个抽屉垫上白色棉花,只放一张旧照。这一张张尘封已久、有些泛黄的照片,或是照相馆家庭合 影,或是单人生活照,或是证件照,或是纪念性集体照,种类、样式丰富,但照片中的人物都是林菁菁的至亲和长辈。林菁菁既把这些照片看作影像家谱和家族志, 又把它们视作与自己生命有关的难得的材料。鉴于对公共隐私的思考,她把这些照片中所有人物的脸部全部挖去。于是,这些老照片上的人物都呈现出一个个至关重 要的漏洞和缺口。人脸被抽空,这些图像独特的隐私属性也就化为乌有。照片只剩下一些了无生气的衣着、家私、建筑和风景。人物只有空壳,但观众惯于用艺术家 自身的肖像去填空。毕竟,他们都是林菁菁的血亲,长相应该与林菁菁相似。遗传学上的依据,让每一张照片人物都变成了林菁菁的化身。林菁菁仿佛以生命轮回的 方式引导观众去体验上个世纪的艰难时世和峥嵘岁月。林菁菁屏蔽家族隐私的武断方法,反倒促成了一种独特图像表达形式,让艺术家自身转为百变精灵,在历史烟 云和现世红尘中任意穿越。也许,就是林菁菁这种难断非此即彼、难分梦里梦外的图像语境,让她生发出“没有人知道我在那,也没有人知道我不在那”的感慨。

林菁菁的《新闻记忆》系列则 从CCTV各种新闻截帧图像中选取。她选择的标准是:画面中必须既有核心人物、又有群众。于是,《新闻记忆》系列的大部分影像都是关于中国官方政治集会、 政治性群众生活的视觉文献,一个个极具仪式化特征的集体活动现场都洋溢着意识形态氛围。林菁菁把每个图片中作为构图焦点的画面核心人物挖掉,再把带缺口的 图像缝制在一个个多孔金属盒上,盒子则盖有带可口可乐商标的盖子。暗示了当下偏右的消费社会背景和偏左的现行意识形态图像的一种冲突。被挖去的核心人物同 样表露出一种存在与缺失的逻辑悖论。那个核心人物的真身已经缺失了,成为艺术家刻意制造的一个公共隐私。虽然具体的个人被艺术家的主观手段屏蔽了,但只要 他的影子还在那,还可以图像现场的中心。不同图像的影子集合在一起,就有了共性,仿佛有一个无处不在的带头大哥,以各种不同动势、姿态掌控着一个个不同的 公共场合。林菁菁企图借此反省公众记忆的集体无意识特性。缺省、省略的结果往往是公众的默认。图像中的核心人物具体是谁并不重要,重要的是人群中必须有这 样的核心人物。

2010-2011的《记忆的颜色》基本上是一件林菁菁直接发掘个人隐私而引发的作品。她设定了三个关于疼痛经验的问题来问身边愿意分享个人隐私的朋 友:1、什么是你最疼痛记忆?2、什么是你与此最疼痛记忆相关的物体?3、哪一种色彩可以用来描述此最疼痛记忆?然后,林菁菁再根据征集来的答案作画。赋 予每张画以特定的色彩、特定的物质对象。这个作品的要素其实就是把个人隐私转化为公共隐私的一个过程。由于艺术家把具体、日常的事物与抽象的色彩混搭,就 把每个个人的隐秘经验转变为一种充满隐喻的视觉符号。而林菁菁这种视觉符号,其实质疑并反讽了公共隐私所塑造的一种日渐肤浅的符号感知模式。个人隐私原本 与公共利益、群体利益无关,但个人隐私转化为公共隐私,就与公众利益息息相关。也许,这就是林菁菁关于隐私的悖论思考。